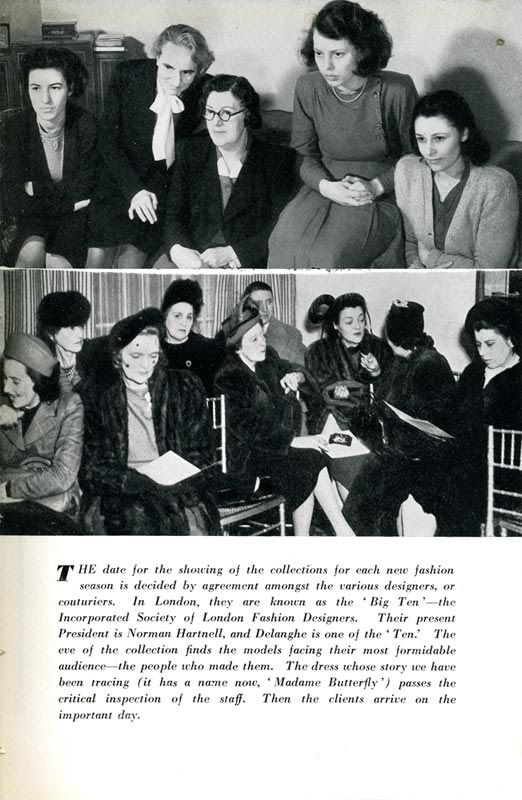

Photograph by Oliviero Toscani from the Sunday Telegraph Magazine, 5 December 1975. Original caption: "Got the message? Back row, from left: Helena Axbey wears a Scratch 'n' Sniff "smelly, £1.80; actress Prunella Gee plumps for Turners on the Strip; model Marianne Desnaux wears an embroidered shirt, £3 from Ace, Kings Road; model Nicki Debuse in Anthony Price's Pink Pussies shirt, £3.25 at Jean Machine; Princess Elizabeth Galitzine sports an Apicella design. Centre row, from left: Alan Pascoe in an original Mods shirt, £1.50 from Scott Lester; art director Geoff Axbey in a Bell telephone shirt, Don Grant in the Hesketh Racing shirt, £2.30; Diana Hyslop in a Marvel Comics number, £1.25; actor Tim Curry wears a Voltar T-shirt, £3.25; Sarah Fox-Pitt of the Tate Gallery in their Coffee Shop shirt, £1.50. Front: Marilyn Cole in a Lips shirt, £9 from Howie, Fulham Road; Ralph Steadman promoting his book; Penthouse Pet Val Mitchell; Enzo Apicella turns Killer for £3.25; Thea Porter wears a rare Yugoslav T-shirt."

This is terribly bad form for someone aspiring to write a blog, but this will be

another post I haven't actually written myself.

When I lived in Brighton a few years ago, I came across a load of old 1970s Sunday supplement magazines scattered over the pavement near a paper recycling bin. Of course I had to take a look, and among them was a

Sunday Telegraph Magazine from 1975 containing the following piece.

Its a wonderful report on the history and language of the t-shirt written by

Anthony Haden-Guest with some great quotes from people involved in their design and production (such as

Anthony Price) and some observations about t-shirts spotted out and about at the time that ring lots of bells for me.

I would have been nine in 1975, so I certainly wasn't in the market for the £9 Howies 'lips' t-shirt (about £56 in today's money, according to

measuringworth.com) but I

did have a scratch 'n' sniff t-shirt with a large strawberry on it - see little Helena in the picture above wearing an apple version - and I'm ridiculously pleased to see it featured in this article. That t-shirt, worn with some very wide C&A jeans with three buttons on each back pocket and two-inch deep turn-ups, and some no-brand canvas basketball boots, was my summer holiday uniform that year.

Enough of my memories, let's get to that article. This is a faithful transcription (I hope), and any emphasis/italicisation was in the original piece.

Anthony Haden-Guest, "The Message Wearers," Sunday Telegraph Magazine, 5 December 1975, pp. 36-40Coco Chanel said it, and cannot be topped. "It doesn't matter how much it costs," observed Mademoiselle, "as long as it looks

cheap." Quite so, and here, stepping through late sunlight down Sloane Street, come three girls. They are, all three of them, wearing T-shirts. The dark one, whom I know slightly, is wearing a ravelled item with the device of a Los Angeles radio station, and the shortish blonde is wearing something pink and frilly with shoulder straps (which does not iron out into that basic cotton T, but is one of the numerous descendants of the T-shirt nonetheless). And the tall girl, also blonde, is wearing a puce number with the following written on it, in italic script:

This is not a T-shirt.

T-shirts. Words and images, swirling and swanning by. The banal and the opaque. The repetitive images - Marilyn, Mickey Mouse, Mao - merging with political slogans, holiday souvenirs, erotica, and the names of obscure American colleges. Household products jostle with rock groups. T-shirts urge love, make dreadful jokes, and communicate Christian names. The ordinary old stretch-cotton T-shirt has spawned a progeny of sequins, glitter, and - in at least one esoteric case - rubber. What started as just low-budget stuff has, unbeknown to itself, burgeoned into a . . . language.

It has, like all languages, its complexities. When Melody Bugner wears the

I'm backing Joe Bugner T-shirt, executed to her own design, her message comes through loud and clear. So, too, when idolatrous garments are worn by the hirelings or fans of the Tate Gallery, Elton John, Marvel Comics, the BBC Proms, the Wombles or

The Economist. Maria Schneider, the French actress, likewise demonstrates her respect for guitarist Eric Clapton by sporting his likeness, just as Charo, current wife of musician Xavier Cugat, sensibly wears her own. Elizabeth Taylor's message -

I am not Elizabeth Taylor so please stop following me - was more complex. And what is one to make of the legend masochistically flaunted by fast bowler Dennis Lillee,

Hit me for six?

Things are even less simple out in the streets. A Coca-Cola T-shirt seldom indicates that the wearer works for that corporation, but there

are corporate T-shirts. A travel T-shirt - Bournemouth, say, or Bermuda - may mean, like a book of matches, that you have been there: or that you would like people to think you have been there, or that the idea of going there is a hilarious joke, or just that you like the image on the shirt.

Some people wear T-shirts because they have bad taste, and some to show what good taste they have by wearing bad taste, like rhinestone-studded images of Elvis Presley. That young man wearing an Ohio State University number is usually a Frenchman who would be hard put to it to locate Ohio on a map; but there is a chance he may actually have been at Ohio State. I assume that the T-shirts lettered Hermès, Vogue and Pierre Cardin are a street-satire, though I am not entirely certain; but I

am certain that the shirts that have, at the bottom, a

trompe l'oeil rendition of a Gucci belt is a joke, and quite a good one at that.

But what of that plumpish lady I once met who bore emblazoned across her frontage a line from a recent hit:

Voulez-vous coucher avec moi ce soir? Ted Polhemus, the American author of a book on fashion-as-language, who was working until recently at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts, notes that "the interesting, and important thing about wearing T-shirts is how much unification of image there is in semiological terms. I saw a girl walking down London's King's Road wearing a T-shirt with people making love all over it. You know, one of those Tantric paintings. What can you say to a girl whose T-shirt shows that? You can't say anything, right? It's an

anti-sexual gesture."

Semiology is, of course, the science of sign language, and Polhemus goes on to note that,

vis-a-vis T-shirts, the signalling extends beyond the image. "Some people just can't wear T-shirts. They

iron them. They always look new. T-shirts should have holes ripped in them. In fact, I used to run a service ripping holes in friends' T-shirts . . . "

It is, in a way, surprising that the language of T-shirts has been massively ignored by fashion historians. Oh yes, the fashion mags (especially the tabloids) do their stuff. But in the hard-cover tomes the T-shirt seldom rates a mention. One recent such I scanned runs from Tabard through every manner of Tricorne and Tunic to a Byzantine something called a Tzitsakson. But T-shirts? Never. The late, and usually commendable, James Laver noted with asperity that jeans and the T-shirt lead us to a world in which, as in Red China, all distinctions of class or sex would be abolished. Even Coco Chanel was, as they say,

parlant d'autres choses.

Which is regrettable, because it is self-evident what T-shirts have become . . . Mass Couture.

There was nothing stylish about the T-shirt's origins, as the upper half of "combinations", but it was charged with a certain frisson. A bit, one imagines, like a blonde in undies; but also a bit like her shopping in curlers. It was this dual brutish aspect that was exploited by the inarticulate Marlon Brando, who, according to Cleveland Amory's

International Celebrity Register, "made a torn T-shirt a symbol of virility". The film was

A Streetcar Named Desire, the date was 1947, and it did not take long for the image to register; the undershirt to encroach on the shirt. It happened, inevitably, in California.

"It was an outgrowth of the Hot Rod culture," says Malcolm MacPherson, a London correspondent for

Newsweek. "It was in the early Fifties. They stopped drag racing on the freeways, and guys were going to the Santa Ana airstrip. You'd see them wearing T-shirts with the names of, you know,

automobiles."

The thing burgeoned. Britain was in one of its phases of acute Americanophilia, and the transatlantic passage of the T-shirt happened so. Marshall Lester, son-and-heir of Scott Lester, who manufactured flags and badges for retail stores, was doodling on a white vest. English, and in his early twenties, he was doodling things American, cities, cars and such, and getting some of them wrong ("Boneville" for Bonneville). But he had them printed and sent them for sale. Just to see.

A couple of days thereafter was the first of the Brighton Mods-and-Rockers riots. Marshall Lester watched it on television. The Mods were wearing his T-shirt. He

saw.

Alan Conway, incidentally, a Lester associate, claims that the blood which was soon to be shed on such T-shirts inspired tie-dyeing. Arguable, though tie-dyeing was certainly the next Big Thing. Chester Martin, a doyen of the field, had managed to acquire a stockpile of the original three-button combination tops, and had them dyed in hip colours. They were to become a basic element in the uniform of another Sixties movement: The Hippies.

The advertisements-for-myself potential of the T-shirt was not overlooked by the Underground. T-shirts proclaiming love, peace, revolution and dope. Coca-Cola and Walt Disney were unamused to find their iconography metamorphosed into, say, Cocaine and Mickey Rat.

Visual inventiveness manifested itself here and there. Already in 1963 painter Allen Jones had produced what may have been the first colour-printed T-shirt. Mr Freedom was creating the first real up-market T-shirts; stylishly brassy pieces exploiting a largely American pop iconography of junk foods and comic strips. "We appreciated American stuff," notes designer Anthony Price, "and they didn't, until

we had done it."

The mass merchandisers began to move in. Record companies tried to transform the uncommitted into fans with free T-shirts, and fans into mobile hoardings. "T-shirts really boomed in 1966," Alan Conway says. World Cup Willie: Carnaby Street: Swinging London souvenirs. "When the mass market got involved everything became very tatty," says T-shirt designer Peter Golding, "The quality was

terrible". Alongside Swinging London, the British T-shirt waned.

But it never died. In spite of fashion journalists, like jeans, it was simply too useful to die. There has been growth, and diversification. At one end of the scale are Marshall Lester, the biggest, and bigger than most American firms, selling projected millions this year. At the other is a small group of designers, and they are bullish. "There's a

rebirth," proclaims Peter Golding, "because it used to be you'd have to do millions, but now it's your custom tailoring. And you can do the very best, and it still shouldn't cost more than £10."

Or there is Malcolm McLaren of the shop formerly entitled Let It Rock, but now called Sex. McLaren has organised a small exhibition of his own T-shirts, including the aforementioned rubber one, and one covered with names of which the designer approves disapproves (your correspondent found himself in the latter category, sandwiched between Alan Brien and

Playboy's London boss, Victor Lownes). Oh yes, and they come carefully pre-torn, or with weakened seams for tearing.

Contrariwise, Anthony Price, who has attracted attention for his Fifties T-shirt look, remarks, "My friends and I were into that James Dean stuff years ago. It's just that now it's commercial. I won't try and sell anything until two years after we're finished with it. It's just a matter of waiting until Mr Average is ready for it."

What is Mr, or Miss, Average ready for right now? "I think the days of being extreme are gone. People don't want to be looked at any more," says Price. And certainly the street look is now a less ornate one; a hearkening back to basic Americana. College shirts and football numerals. "After all that glitter," muses Andrew Bailey, former London Editor of

Rolling Stone, now with Bell Records, "It's quite nice to look like a clean-cut college boy. Even if it's not a college you went to . . ."

And things to come? "Los Angeles is always first, and

Paris," says John Dove of Wonder Workshop firmly (Dove has designed some splendidly garish pin-uppy designs). "London's bad-taste level is about one year behind. And Germany's bad-taste level is two years behind us. We sell a lot to them. Rock-n-roll stuff, and they're really into glitter. Next I think Pop is going to be coming back. I foresee a big revival."

Or, to be accurate, a revival of a revival. The T-shirt has accumulated a history. "I still wear my 1973 Rolling Stones Tour T-shirt," says Andrew Bailey. "It's like a - campaign ribbon." The T-shirt as memoir, but there's more to it than this. There are T-shirt collectors who have amassed hundreds, and not merely the rare expensive item, like the early Beatles number recently sold for £85. But T-shirts collected for their associations, their sheer power of image. The

classics.

Like the T-shirt with the image of the slung Nikon camera, and the one from Biba's which had the bust-size in sparkly numbers. Or, for that matter, the one with two fried eggs positioned over the boobs; or a close focus photograph of the torso (the T-shirt, that most physically revealing of upper garments, is still oddly obsessed with physicality). Or the Mona Lisa T-shirt, or the defunct line of

Private Eye T-shirts, or the T-shirt across the front of which breaks one of Hokusai's woodcut waves. Or the T-shirt which carries a

trompe l'oeil rendition of a dinner-jacket and black tie. Or the one which said

I'm backing Britain, or that more recent political classic which bore the legend

Gather Strength and was to have been worn by four young women from the Amalgamated Textile Workers' Union lined up in a comradely way alongside leading Labour politicos, until they noticed the labels said Made in Portugal.

Innovation, meanwhile, continues. Consider the "smellies", as developed by the 3M Corporation of Minnesota. In our picture (back left) Helena Axbey is wearing a Scratch 'n' Sniff apple, as marketed by Scott Lester. Scratch, and, yes you do sniff apple, and Conway assures me that the shirt will last many hard washes.

Nor does it stop with apples. There's oranges and strawberries. "We're hoping to do something for Coca-Cola. Do you want to smell it? Amazing, isn't it? We've got chocolate, petrol, gas. The gas is revolting. We wouldn't use it on a T-shirt. They can make the smell of anything. Except beer and coffee . . . "

Now upon us also is the iron-on. Images are published in U.S. newspapers which can be ironed on to the T-shirt directly. Just so. Coco Chanel was right. Mass couture. And it is only occasionally that my mind drifts to this cartoon published in last June's

The New Yorker.

[I neglected to photograph this. The cartoon shows a young man walking along a beach crowded with people wearing slogan t-shirts. His t-shirt is blank and his girl companion says: "Nonsense! I think it's refreshing to see a T-shirt that doesn't say anything."]