Finding historic accounts of men's fashions can be a challenge. For the most part, women's fashions dominate surviving records for obvious reasons: fashion has long been assumed to be a largely feminine preoccupation, women's fashions have a faster turnover of trends so there's always some new novelty to observe, and they tend to be more dramatic and eye-catching. Equally, while a woman's appearance was (and frequently still is, sadly) considered to be the most pertinent and interesting aspect of her being, a man's appearance was taken to be the least important thing about him, unless it was particularly remarkable or curious. Men were judged, and recorded, on different criteria - skills, talents, character, achievements - with their wardrobe coming very low on the list, if at all.

As a result, there's a real lack of detailed descriptions of everyday men's wear since it was usually considered of no importance or relevance. Which is why this short piece, 'Frenchmen's Fashions,' published in the seventh Saturday Book in 1947, is such a treasure. Written by Honor Tracy, it provides a precious snapshot of men's fashions in Paris in the immediate post-war period.

Showing posts with label 1940s. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 1940s. Show all posts

Monday, 24 January 2011

Frenchmen's Fashions, 1947

Labels:

1940s,

dress history,

fashion,

France,

menswear,

military surplus,

Paris,

Second World War

Sunday, 1 August 2010

The Story of a Dress

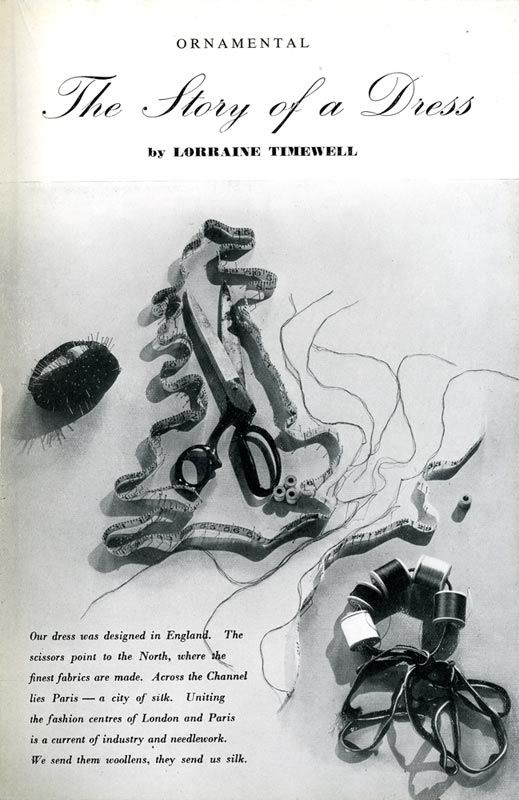

"The Story of a Dress" by Lorraine Timewell, The Saturday Book 7, 1947, pp. 71-80.

Our dress was designed in England. The scissors point to the North, where the finest fabrics are made. Across the Channel lies Paris - a city of silk. Uniting the fashion centres of London and Paris is a current of industry and needlework. We send them woollens, they send us silk.

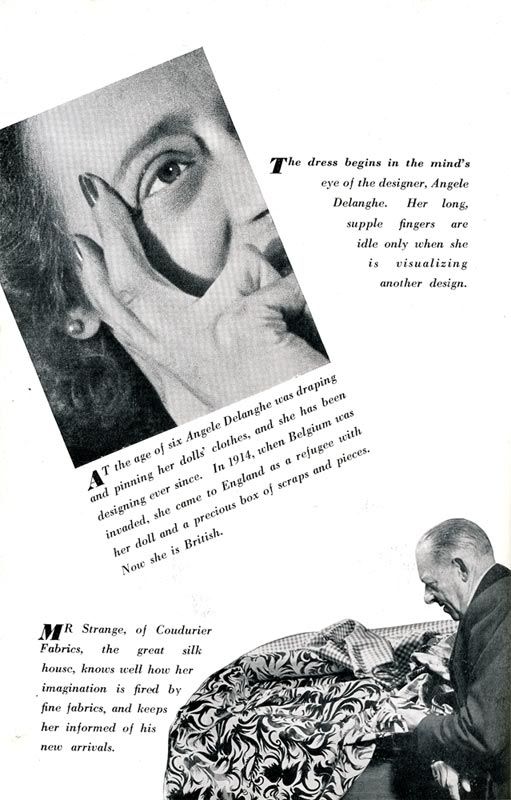

The dress begins in the mind's eye of the designer, Angele Delanghe. Her long, supple fingers are idle only when she is visualizing another design.

At the age of six Angele Delanghe was draping and pinning her doll's clothes, and she has been designing ever since. In 1914, when Belgium was invaded, she came to England as a refugee with her doll and a precious box of scraps and pieces. Now she is British.

Mr Strange, of Coudurier Fabrics, the great silk house, knows well how her imagination is fired by fine fabrics, and keeps her informed of his new arrivals.

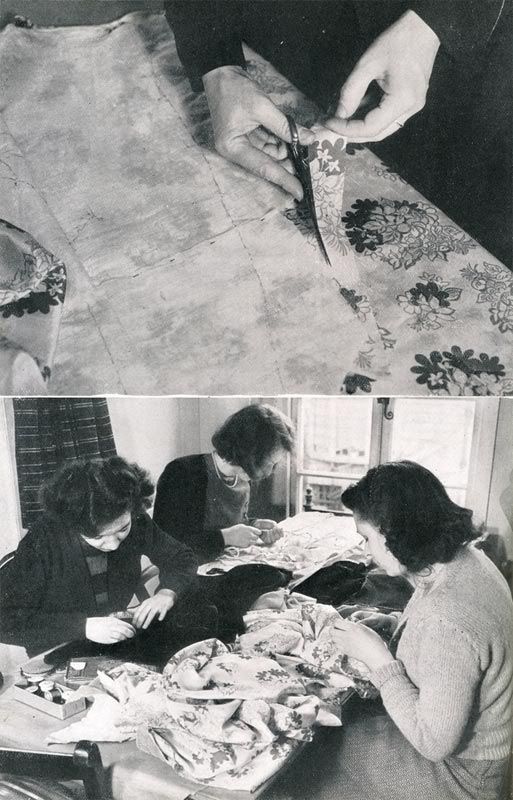

In a tiny room she works with the selected fabric straight onto the dummy, its shoulder scarred with pin-marks. In picture one, she is concentrating her mind not on the checked silk, but on the floral printed silk lying on the table by Smuts the cat. She knows exactly what she wants to do with it, and in picture two begins to drape and pin. It is a fine silk in a pale oyster white, with burnt rose and grey outlined flowers scattered over it.

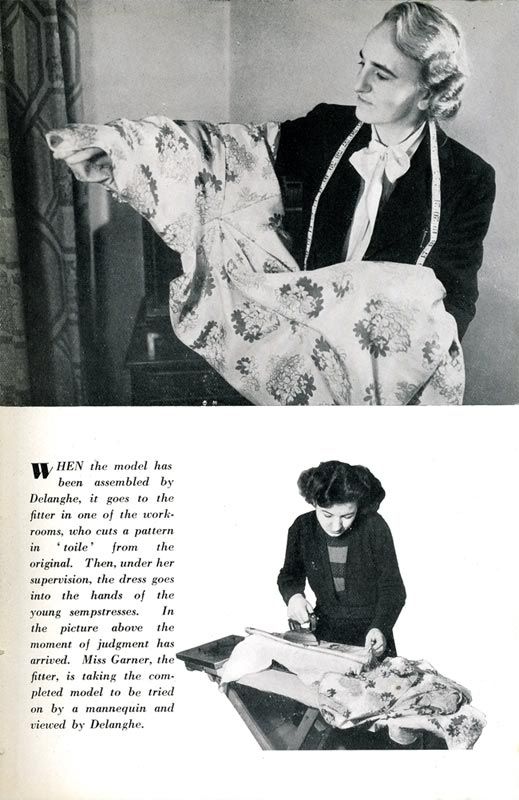

When the model has been assembled by Delanghe, it goes to the fitter in one of the workrooms, who cuts a pattern in 'toile' from the original. Then, under her supervision, the dress goes into the hands of the young sempstresses. In the picture above the moment of judgment has arrived. Miss Garner, the fitter, is taking the completed model to be tried on by a mannequin and viewed by Delanghe.

Audrey Kenney, the mannequin, with her head in a bag, is helped into the dress. The bag protects the fabric from lipstick and powder, and protects also her new 'hair-do.'

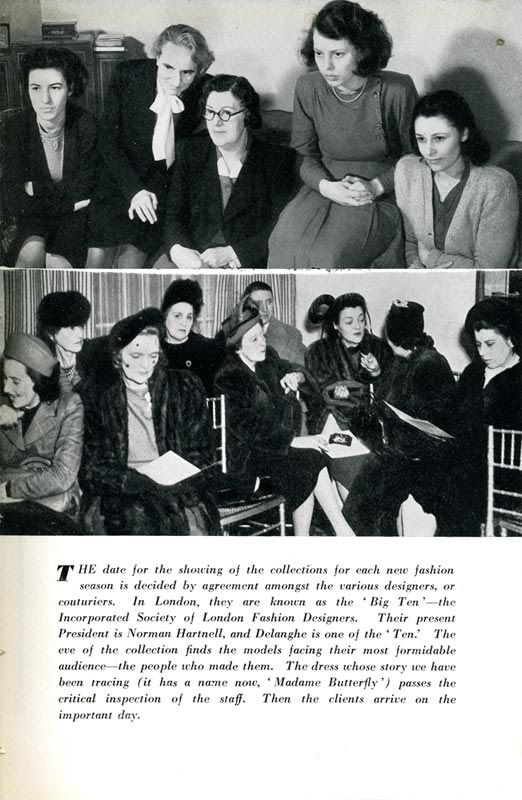

The date for the showing of the collections for each new fashion season is decided by agreement amongst the various designers, or couturiers. In London, they are known as the 'Big Ten' - the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers. Their present president is Norman Hartnell, and Delanghe is one of the 'Ten.' The eve of the collection finds the models facing their most formidable audience - the people who made them. The dress whose story we have been tracing (it has a name now, 'Madame Butterfly') passes the critical inspection of the staff. Then the clients arrive on the important day.

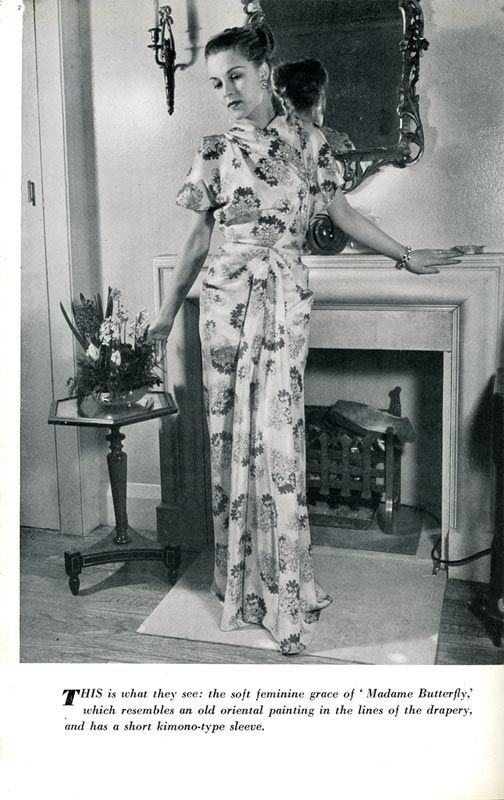

This is what they see: the soft feminine grace of 'Madame Butterfly,' which resembles an old oriental painting in the lines of the drapery, and has a short kimono-type sleeve.

They also see 'Madame Butterfly's' 44 companions, including its opposite number, 'Gleneagles.' Some of the models are never again seen in England: they go to the United States and elsewhere abroad.

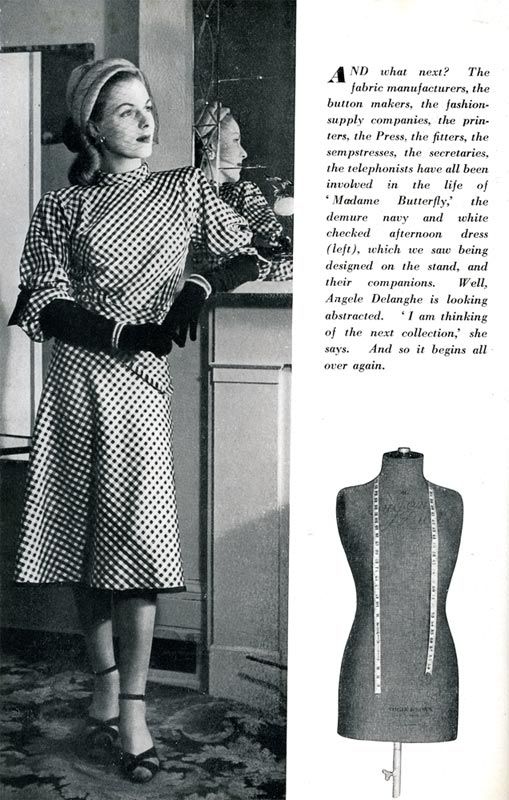

And what next? The fabric manufacturers, the button makers, the fashion-supply companies, the printers, the Press, the fitters, the sempstresses, the secretaries, the telephonists have all been involved in the life of 'Madame Butterfly,' the demure navy and white checked afternoon dress (left), which we saw being designed on the stand, and their companions. Well, Angele Delanghe is looking abstracted. 'I am thinking of the next collection,' she says. And so it begins all over again.

_._._._._._._._._._._._._._._._._._._

This photo story appeared in the seventh edition of The Saturday Book - one of those compendiums of miscellany from the arts to anthropology, history and antiquities, social observation, folklore and all manner of diverting stuff - that were once so popular.

This edition was published in 1947, at pretty much the height of post-wartime austerity and a time when most women could only dream of a new evening gown made of silk, so its interesting to see that Ms Delanghe appeared to have no problem securing such scarce and valuable supplies. But then, as the piece points out, some (most?) of her output was destined for export.

Its great to see that the author, Lorraine Timewell, chose to feature Angele Delanghe rather than one of the more well known members of the London 'Big Ten' such as Hartnell, Hardy Amies or Digby Morton.

In fact I've found precious little about her, apart from these scraps:

Delanghe was an early member of the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers, formed in 1942, which included the Hon. Mrs Reginald Fellowes (its first president), Norman Hartnell, Peter Russell, Worth of London, Digby Morton, Hardy Amies, Bianca Mosca, Creed, Molyneux and Michael Sherard. (Information from In Vogue: Six Decades of Fashion by Georgina Howell and Exploring 20th Century London).

She was known for creating "soft feminine tailored clothing and beautiful romantic eveningwear and wedding gowns" (from The Cutting Edge: 50 Years of British Fashion, 1947-1997 by Amy de la Haye).

After the war she took over the Ladies' Outfitting and Ready to Wear Departments at Fortnum & Mason and "revitalized" them.

Former women's editor of the Yorkshire Post, Valerie Webster, recalls with palpable frustration that she was required to attend "the couture shows of people like Angele Delanghe and Lachasse who made tweedy suits and hefty jewel-encrusted evening gowns for the grouse moors and hunt ball scene." To be fair, this was probably in the early 1960s, and young Valerie was more interested in Mary Quant than grouse moors and hunt balls, and perhaps Delanghe was past her prime.

This little 'backstage' story of Angele Delanghe's work at least adds a little more to our knowledge of her.

Labels:

1940s,

Angele Delanghe,

dress history,

fashion designers,

haute couture,

London

Wednesday, 31 March 2010

Daffodils and memories

1940s lady - hand tinted photograph, originally uploaded by Trevira.

This beautiful photograph is a hand tinted 8x10 dating from the 1940s, possibly during the Second World War. A very stylish and attractive woman sits in a picturesque country setting, surrounded by daffodils. She looks so happy.

Its only when you turn it over that this photograph zaps you with something quite unexpected and moving. On the back is written: "Looking at this now - I realise I was carrying my daughter - how I wish those times could have given me the courage to ignore the moral issues and let nature take its course."

Suddenly its hard to look at that picture in quite the same way. I imagine this woman was going through her photographs some years later and felt the need to record her regret at the loss of her daughter, perhaps for herself or for her family. Or just to memorialise her child. Her daughter was there in that photograph, only we couldn't know that by just looking at the picture, and neither did she at the time.

I found this photograph among a whole boxful from the same family, and bought as many as I could afford. Its clear that they later had a son whom they doted on, and enjoyed many happy times and holidays together as a family. I would like to add some more pictures of the family here, or at least links to them, but trying to do both things resulted in me losing all the text I had written in a mass of tangled HTML. So I daren't!

Shuffling through the pictures you would assume this was a very happy family living a very uncomplicated and picture perfect life, but that little note is a sharp reminder that things aren't always that straightforward.

Labels:

1940s,

family,

history,

memory,

old photograph

Friday, 19 February 2010

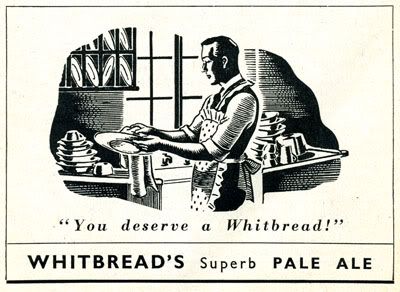

You deserve a Whitbread!

This startling advertisement appeared in Lilliput magazine's June 1947 issue. A man is pictured in a frilly apron doing the washing up, presented with no comment or indication that this is the least bit remarkable.

Taken in the context of the immediate post-war years, it did surprise me. Men were returning from fighting six long years of war and the usual story we are told is that women who had ably coped with 'men's' jobs - working in munitions and aeroplane factories during the war - were immediately pushed out of their jobs and ordered back into the home and kitchen where they belonged. It was back to 'business as usual' - the reassuring gendered division of labour with women as housekeepers and mothers, men as breadwinners, and pampered kings of the castle at home.

This ad complicates those assumptions. There's no suggestion that this man is emasculated by helping out at home, even with a frilly apron on, and the scenario is not exploited for comic effect (as it inevitably would be today). In fact he looks rather noble in his woodcut-style vignette. Perhaps gender roles in the post-war years were a little more complicated and nuanced than we have been led to believe by most popular histories.

Of course, I'm sure most women wouldn't have expected to be rewarded with a bottle of pale ale for doing household chores, so there's an indication that the man's efforts are a little bit special, although obviously not unusual.

In fact, within a few pages of the same magazine is another very similar advertisement:

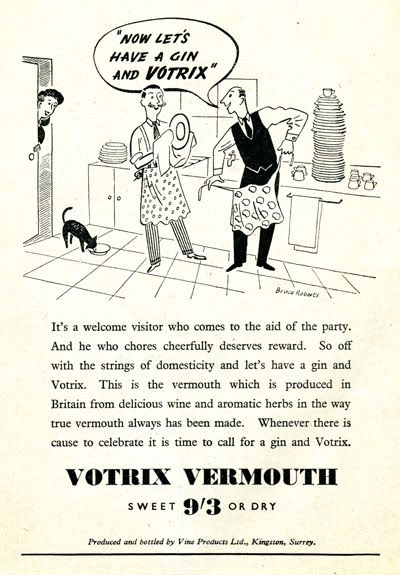

Votrix Vermouth advertisement in Lilliput, June 1947, page iii.

Votrix Vermouth advertisement in Lilliput, June 1947, page iii.The occasion this time is the aftermath of a party, with two gentlemen gamely tackling the piles of dishes. They both wear feminine, patterned aprons and are again deserving of a reward in the form of an alcoholic drink. A delighted-looking wife peers through the door (and then perhaps runs off to fetch their drinks?!)

Did men do anything else around the home except the dishes, now and then? Perhaps . . .

Did men do anything else around the home except the dishes, now and then? Perhaps . . .

This vacuum cleaner advertisement from the same year is rather less credible ("Give him a Vactric"? Hmm) and there is a lightly ironic tone to the copy: "When the household god descends to lend a hand" is a clear indication of the 'normal' domestic power relationship, however humorously expressed.

So the idea of a man helping out with onerous domestic chores is framed in all these advertisements as a sort of special treat for their wives, who are still expected to do them most of the time. But at least its not portrayed as ridiculous or unmanly, as you might expect even to this day, and its considered unremarkable enough to be featured in mainstream advertising.

It makes me wonder how far we've progressed since then (as I contemplate the stairs that need vacuuming . . .)

Labels:

1940s,

advertisement,

gender,

history,

masculinity

Thursday, 4 February 2010

Fashion rations

Even during the dark years of the Second World War, and the long years of clothing rationing that followed it, women were expected to keep up appearances. "England's number one glamour girl" Joan Richards, a professional model, doesn't disappoint in this 1944 film where we follow Joan through a "routine day's work." From getting up in the morning with full slap (apologies to US readers - slap = makeup) and immaculate hair, through her long and busy day, she is the epitome of 1940s chic. By the way, these film links have come up as black boxes, but they will work if you click on them.

However, not every woman met the grade. This amusing short from September 1946 features the "Pathé Pictorial Fashion Expert" Mr Richard Buzzvine (at least, that what his name sounds like) lurking self-consciously with a newspaper on Regent Street as he casts a waspishly critical eye over young women's outfits. Although his voice isn't heard, the narrator reports his merciless judgements.

Mr Buzzvine is very hard to please, and only one girl meets with his approval, although its hard to see how she is much different from the other 'failures.' Its a useful reminder of how fraught getting dressed used to be, with all kinds of complicated rules and conventions governing what was - and was not - appropriate wear.

ANNE EDWARDS (aka GLAMOUR GIRL)

However, not every woman met the grade. This amusing short from September 1946 features the "Pathé Pictorial Fashion Expert" Mr Richard Buzzvine (at least, that what his name sounds like) lurking self-consciously with a newspaper on Regent Street as he casts a waspishly critical eye over young women's outfits. Although his voice isn't heard, the narrator reports his merciless judgements.

Mr Buzzvine is very hard to please, and only one girl meets with his approval, although its hard to see how she is much different from the other 'failures.' Its a useful reminder of how fraught getting dressed used to be, with all kinds of complicated rules and conventions governing what was - and was not - appropriate wear.

RIGHT AND WRONG IN FASHION

Labels:

1940s,

British Pathé,

dress history,

fashion,

film,

rationing,

Second World War,

video,

women

Tuesday, 22 December 2009

Are you dancing? Are you asking?

Christmas is the prime party season, and parties often involve dancing. Which gives me another opportunity to plunder the vaults of British Pathé for some vintage treasures on that very theme.

Ballroom dancing is fraught with dangers - where do I put my hands? What frock should I wear? Which foot goes first? - so here's a helpful, unnamed dance instructor to put you right in a very prim short filmed at the Empress Room, Kensington, London in 1938.

Watch out for the swing step that's "hot from Harlem" but, the narrator warns, is "rather too hot for English ballrooms":

The "English style" mentioned was developed by English dance teachers' organisations to regulate and tame the wild new dances coming from the United States, and was explicitly intended to eliminate any aberrant moves such as kicks or swinging hips, or indeed anything that smacked of self-expression, sexuality or spontaneity.

In the crowded conditions of most English dancehalls at this time, it could be argued that some control was needed to preserve the smooth rotation of dancing couples around the floor without things ending up in fisticuffs over collisions and painfully stomped feet. But the efforts of the dance instructors drained nearly all the personality and unique appeal (not to mention the fun) of these dances to the extent that it was difficult to discern one dance from the other.

We need an antidote to all that prim English reserve. And Earl and Josephine Leach, in this 1937 film demonstrating an hilarious version of the Big Apple, are here to supply it. They gleefully break all the rules:

This was precisely the time - the late 1930s - when dance hall managers realised that the sterling efforts of those dance instructors had succeeded in making many patrons scared of taking to the floor in case they committed a dreadful faux pas and showed themselves up. Dancing was in danger of becoming a difficult exercise only to be attempted by trained experts.

As a result, dance hall proprietors (including the dominant Mecca Ballroom chain) actively encouraged the development of easy dances that anyone could do after watching a short demonstration.

Watch this short film, shot at the Streatham Locarno (south London) in 1938, and you too will be able to do the Lambeth Walk with confidence:

Of course, what was around the corner was the all-conquering Jitterbug, which ruled British dance floors during the Second World War, and wasn't actually that easy to do well. But we had a useful influx of US servicemen to teach us how to do it properly.

This fun film - from Youtube rather than British Pathé this time - shows MGM's comic take on the dance craze in 1944:

Make sure you clear away all furniture and breakables before you attempt this at home.

Additional notes

This post neglects the original pioneers of most of these dances, the African-American community, which is sorely under-represented in the British Pathé archive. OK, that's probably understandable since it was a UK based operation. This post shows how their dances were interpreted on this uptight little island. But I can't let this pass without some acknowledgement, so here goes.

My all-time favourite dance sequence of all time is this clip from the 1941 film Hellzapoppin' featuring Slim and Slam and the Harlem Congaroos (I'm sure its many other people's favourite too, but it doesn't hurt to repeat it) which is approximately five minutes of pure joy. If you've never seen it before, prepare to be amazed:

Ballroom dancing is fraught with dangers - where do I put my hands? What frock should I wear? Which foot goes first? - so here's a helpful, unnamed dance instructor to put you right in a very prim short filmed at the Empress Room, Kensington, London in 1938.

Watch out for the swing step that's "hot from Harlem" but, the narrator warns, is "rather too hot for English ballrooms":

DANCING

The "English style" mentioned was developed by English dance teachers' organisations to regulate and tame the wild new dances coming from the United States, and was explicitly intended to eliminate any aberrant moves such as kicks or swinging hips, or indeed anything that smacked of self-expression, sexuality or spontaneity.

In the crowded conditions of most English dancehalls at this time, it could be argued that some control was needed to preserve the smooth rotation of dancing couples around the floor without things ending up in fisticuffs over collisions and painfully stomped feet. But the efforts of the dance instructors drained nearly all the personality and unique appeal (not to mention the fun) of these dances to the extent that it was difficult to discern one dance from the other.

We need an antidote to all that prim English reserve. And Earl and Josephine Leach, in this 1937 film demonstrating an hilarious version of the Big Apple, are here to supply it. They gleefully break all the rules:

THE BIG APPLE

This was precisely the time - the late 1930s - when dance hall managers realised that the sterling efforts of those dance instructors had succeeded in making many patrons scared of taking to the floor in case they committed a dreadful faux pas and showed themselves up. Dancing was in danger of becoming a difficult exercise only to be attempted by trained experts.

As a result, dance hall proprietors (including the dominant Mecca Ballroom chain) actively encouraged the development of easy dances that anyone could do after watching a short demonstration.

Watch this short film, shot at the Streatham Locarno (south London) in 1938, and you too will be able to do the Lambeth Walk with confidence:

NEW DANCES FOR EVERYBODY

Of course, what was around the corner was the all-conquering Jitterbug, which ruled British dance floors during the Second World War, and wasn't actually that easy to do well. But we had a useful influx of US servicemen to teach us how to do it properly.

This fun film - from Youtube rather than British Pathé this time - shows MGM's comic take on the dance craze in 1944:

Make sure you clear away all furniture and breakables before you attempt this at home.

Additional notes

This post neglects the original pioneers of most of these dances, the African-American community, which is sorely under-represented in the British Pathé archive. OK, that's probably understandable since it was a UK based operation. This post shows how their dances were interpreted on this uptight little island. But I can't let this pass without some acknowledgement, so here goes.

My all-time favourite dance sequence of all time is this clip from the 1941 film Hellzapoppin' featuring Slim and Slam and the Harlem Congaroos (I'm sure its many other people's favourite too, but it doesn't hurt to repeat it) which is approximately five minutes of pure joy. If you've never seen it before, prepare to be amazed:

Labels:

1930s,

1940s,

British Pathé,

dance hall,

dancing,

film,

Harlem Congaroos,

Hellzapoppin',

instruction,

jitterbug,

lindy hop,

movie,

Slim and Slam

Thursday, 17 December 2009

Lend me your elephant's ear - and I'll make a bag out of it

My last post was a complete failure as a viable Christmas gift idea for all kinds of reasons - let alone the fact that the fishtank was from a catalogue that was about 50 years old - so I've decided to make amends with some more promising prospects for the lady in your life.

Sadly most of these are from more or less the same date or even earlier so you've the same chance (exactly none, unless you are a very accomplished vintage buyer) of finding them.

If you've read any of the previous posts you will know that I am an ardent fan of the British Pathé film archive, so I'm happy to present a few more gems that I have gathered from their amazingly extensive collection.

First up is a delightful film from 1946 about what the narrator cheerfully refers to as "junk" jewellery, which would probably be classed as "costume" jewellery these days.

Apologies for not being able to embed these films but, trust me, they are all worth the bother of opening a new tab or window to view (you can complain in the comments if they're not!):

And continuing on the earrings theme is this film from 1955 (in glorious Technicolour!) which showcases the stock of a Soho shop called "Going Gay" and is essential viewing for anyone who appreciates 50s kitsch jewellery:

There's some very dubious parallels drawn with ancient civilisations and ethnic cultures by the narrator, but they're easy to ignore with all those marvellous baubles to enjoy.

Another potential gift idea is a handbag, an item that most women can't have too many of.

In the following 1955 film you are first presented with a pink handbag made out of elephants' ears. Control your nausea - and please don't worry, there's nothing distressing shown - because this is a terrific film with some prize examples that really shouldn't be missed, including something for the dipsomaniac gentleman:

Spectacles might not be your first thought for a gift, but bear with me here because this is a fantastic 1955 film with some extraordinary examples of eye-wear.

Its hard not to be distracted by the flying hands of the optician who seems to swoop over every woman featured with dramatic and energetic gestures - I'm sure he's making some interesting and informative points, only we can't hear them:

Finally, if you've ever wondered what spectacles might be suitable for motoring and the beach you have your answer in the last few seconds of this film:

Lucie Clayton's was a finishing/modelling school in London for very posh 'gels' (Joanna Lumley among them) which has recently been amalgamated with two secretarial colleges to form Quest Business Training. I'm pretty sure classes in "Spec Beauty" aren't part of the current curriculum.

Sadly most of these are from more or less the same date or even earlier so you've the same chance (exactly none, unless you are a very accomplished vintage buyer) of finding them.

If you've read any of the previous posts you will know that I am an ardent fan of the British Pathé film archive, so I'm happy to present a few more gems that I have gathered from their amazingly extensive collection.

First up is a delightful film from 1946 about what the narrator cheerfully refers to as "junk" jewellery, which would probably be classed as "costume" jewellery these days.

Apologies for not being able to embed these films but, trust me, they are all worth the bother of opening a new tab or window to view (you can complain in the comments if they're not!):

EAR-RINGS [sic] (aka JUNK JEWELLERY)

And continuing on the earrings theme is this film from 1955 (in glorious Technicolour!) which showcases the stock of a Soho shop called "Going Gay" and is essential viewing for anyone who appreciates 50s kitsch jewellery:

PARTY EARRINGS

There's some very dubious parallels drawn with ancient civilisations and ethnic cultures by the narrator, but they're easy to ignore with all those marvellous baubles to enjoy.

Another potential gift idea is a handbag, an item that most women can't have too many of.

In the following 1955 film you are first presented with a pink handbag made out of elephants' ears. Control your nausea - and please don't worry, there's nothing distressing shown - because this is a terrific film with some prize examples that really shouldn't be missed, including something for the dipsomaniac gentleman:

LEATHER FAIR

Spectacles might not be your first thought for a gift, but bear with me here because this is a fantastic 1955 film with some extraordinary examples of eye-wear.

Its hard not to be distracted by the flying hands of the optician who seems to swoop over every woman featured with dramatic and energetic gestures - I'm sure he's making some interesting and informative points, only we can't hear them:

SPECTACLES

Finally, if you've ever wondered what spectacles might be suitable for motoring and the beach you have your answer in the last few seconds of this film:

MODELS LEARN SPEC BEAUTY (aka SPECTACLE FASHION)

Lucie Clayton's was a finishing/modelling school in London for very posh 'gels' (Joanna Lumley among them) which has recently been amalgamated with two secretarial colleges to form Quest Business Training. I'm pretty sure classes in "Spec Beauty" aren't part of the current curriculum.

Labels:

1940s,

1950s,

belt,

British Pathé,

costume jewellery,

earrings,

fashion,

film,

glasses,

history,

spectacles,

tiara,

video

Sunday, 15 November 2009

Upcycling, recycling, remaking, reusing

hand made antique dolly peg, originally uploaded by Trevira. This is made of a strip cut from an old tin, wound round a split stick.

In principal its ALL good, but having recently joined Etsy I've had reason to give it some more thought.

There's a lot of people busily remaking new garments out of vintage ones, and some of them are remarkably inventive and stylish. But I do have qualms about using, and drastically altering, vintage items that are perfectly wearable and undamaged as they are.

In their original state, they are authentic survivors of their era, and often have some value as collector's items or potential museum pieces. Once they have undergone such alterations, they are no longer authentic, and have lost that intrinsic value accrued by age, rarity and desirability - but on the other hand, they may have gained in appeal for the modern buyer who isn't the least bit interested in history or authenticity.

Of course, reusing and remaking clothing is nothing new. For centuries, people have plundered old, secondhand garments - unpicked silk dresses to remake the valuable fabric into something new; removed lace collars and trimmings to adorn another blouse or dress; snipped off buttons and saved them for the next suitable sewing project.

As fashions changed, garments might be altered to conform to the newest styles. When paisley cashmere shawls fell out of favour in the nineteenth century, for example, some of them ended up as neat little jackets or mantles. Here's a late example from the 1920s, held at the Gallery of Costume, Manchester.

In the days before 'vintage' became the lucrative marketing term it is today (something I've discussed rather pompously here), nobody was sentimental about secondhand clothing, regarding it as raw material to be used as they saw fit.

So perhaps I shouldn't be bothered. But the historian in me can't help but mourn the loss of items that have survived the years intact, only to be destroyed at the hands of some unsympathetic maker who is perhaps blind to its merits. (There is a case to be made, I suppose, that the 'new' items made from old ones become authentic artefacts of the current era).

That said, I find it hard to care about mass produced 1980s garments - they're not that old, they're plentiful and most of them are pretty dreadful (I'm being unforgivably subjective here!). Perhaps in twenty years I might feel differently.

My parameters for justified reuse are: badly damaged and/or worn out garments - or ones less than twenty years old - that have no particular qualities, uniqueness or style to them are fair game.

Admittedly, this is probably still ridiculously irrational and sentimental of me. Especially since I have quite a number of vintage clothes in my wardrobe that I wear on a regular basis and will eventually wear out and (effectively) destroy myself!

The era most associated with reusing and remaking garments is that of the Second World War - when 'make do and mend' was an imperative that no-one could afford to ignore. Goodness knows how many potentially valuable 'vintage' items ended up chopped up or altered (like my first ever vintage dress, which got off relatively lightly) during that time.

Anne Edwards, fashion editor of Woman magazine, provides some ingenious tips on how to decimate your poor husband's wardrobe while he is off fighting the war, in this 1942 British Pathé clip (this film might account for the relative scarcity of 1930s menswear!):

HATS (aka MAKE AND MEND HATS)

Even women's wardrobes weren't safe from the scissors! An evening dress is transformed into a becoming day dress (and turban):

EVENING AND DAY FROCK (issue title is HI-DE-HI)

And finally, "great grandma's priceless old lace" is turned into some attractive household decor items:

LACE (issue title is GIVE AND TAKE)

Labels:

1940s,

authenticity,

British Pathé,

clothing,

film,

history,

movie,

recycling,

remaking,

Second World War,

sewing,

value,

vintage

Saturday, 14 November 2009

How do you advertise when you don't have anything to sell?

Leafing through a copy of Modern Woman magazine from January 1944, I noticed that a number of the advertisements weren't promoting actual goods, but the promise of them after the war.

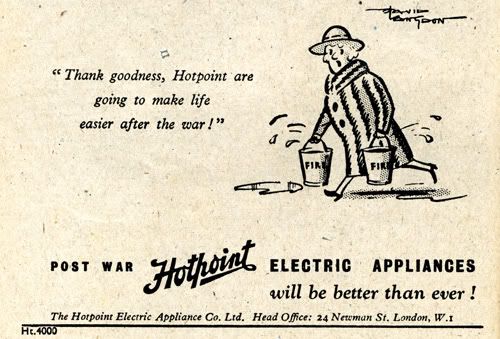

The frazzled lady above with the fire buckets is presumably doing the weekly wash, and couldn't wait until she was able to buy a new Hotpoint washing machine, something that I'm sure a lot of women at the time could relate to.

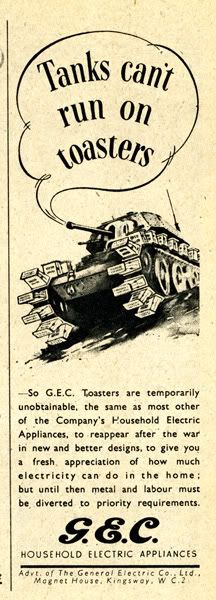

G.E.C. (below) used an arresting illustration to make the point that their production lines were diverted to munitions work for the duration:

Clothing manufacturers, such as Healthguard knitwear, were busy supplying the troops with uniforms and (presumably in this case) cosy and durable knitted sweaters and undergarments, although in this industry, unlike that of the electrical manufacturers, a small proportion of their output was devoted to the domestic market:

The tone is sympathetic but encouraging - acknowledging that their products will be scarce and probably require a concerted effort to hunt around numerous retailers to source - "annoying, perhaps, but well worth the bother." (I can't see that phrase catching on in the same way as "Keep calm and carry on," somehow).

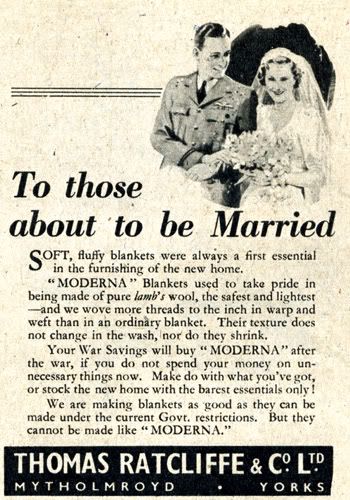

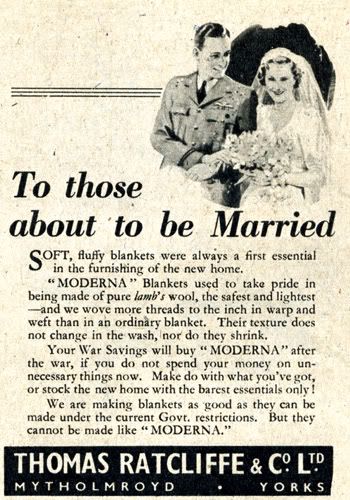

Thomas Ratcliffe & Co. Ltd., makers of Moderna wool blankets, appear concerned to preserve their image as producers of high quality goods:

After explaining what makes their blankets so special - "pure lamb's wool . . . more threads to the inch in warp and weft than in an ordinary blanket" - they are obliged to confess that their wartime blankets, produced "under the current Govt. restrictions," aren't quite so special. In fact, its clear they really don't want to sell you their current, substandard blankets at all and instead urge wartime brides who are setting up their new homes to save their money for the (better) post-war Moderna blankets and in the meantime "make do with what you've got"!

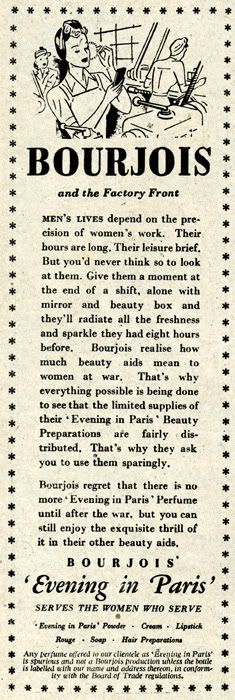

Bourjois, the cosmetics manufacturer, congratulates women on maintaining their feminine allure whilst engaged in arduous war work, but urges them to use their scarce products sparingly:

In small print at the bottom, after expressing regret that their Evening in Paris perfume will not be available during the war, is this warning: "Any perfume offered to our clientele as 'Evening in Paris' is spurious and not a Bourjois production unless the bottle is labelled with our name and address thereon, in conformity with the Board of Trade regulations."

It seems that shoddy, counterfeit goods were another hazard of wartime life.

All these adverts appeared in a single magazine in 1944, five years into the Second World War, and their message must have been repeated throughout countless publications during the conflict. Although manufacturers engaged in essential war production were probably not suffering unduly, with their lucrative Government contracts, they were evidently anxious to maintain public goodwill and the future customer base that would ensure their post war prosperity.

For consumers, it must have been constantly frustrating to be repeatedly reminded about what they didn't have and couldn't get. Everything had to wait until after the war.

But what nobody seemed to realise (or perhaps didn't dare admit) was that all these enticing goods wouldn't suddenly appear in the shops once victory was declared in 1945. In fact, shortages and rationing got much worse! The government had huge wartime debts and just about anything worth selling was exported to help pay it off.

After six long years of deprivation, not to mention the stress and heartbreak of living through a long and bitter world war, the patient and enduring British consumers were faced with a further nine years wait before all rationing finally ended in 1954.

Of course, they weren't necessarily that patient and enduring (who would be?) If you want to learn more about the 'ordinary' British person's experience of the immediate post war years, you can't do better than Simon Garfield's book Our Hidden Lives. Garfield skilfully and sensitively edits the Mass Observation diaries of five people to illustrate how this largely overlooked era affected those five individuals, and it makes surprisingly vivid and compelling reading.

An aspect of wartime advertising I haven't mentioned yet, is the manufacturers' awareness of the limits of that assumed patience. An Atkinsons Eau de Cologne ad pleads: "Supplies are scarce though, so please don't be cross if the shopkeeper is out of stock." A Parozone bleach ad urges: "Don't blame your suppliers if you can't get all the Parazone you want. Bear with us please - we are doing everything possible to maintain supplies."

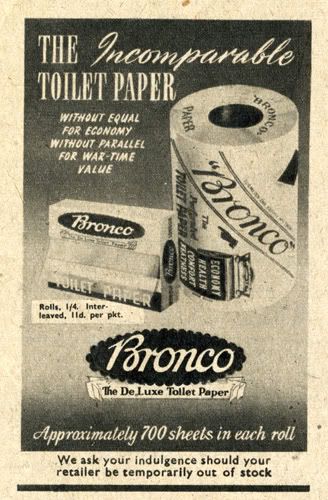

There's a clear hint of the daily, small-scale conflicts that poor, hard-pressed shop staff had to face from frustrated and enraged shoppers. But, I ask you, could you tolerate this?:

At the bottom of this advertisement it says: "We ask your indulgence should your retailer be temporarily out of stock." My memories of Bronco are of the waxy, stiff and resolutely non-absorbent toilet paper that no-one would buy or use out of choice. To have only Bronco toilet paper available is torture enough. To have no toilet paper at all is beyond comprehension!

At the bottom of this advertisement it says: "We ask your indulgence should your retailer be temporarily out of stock." My memories of Bronco are of the waxy, stiff and resolutely non-absorbent toilet paper that no-one would buy or use out of choice. To have only Bronco toilet paper available is torture enough. To have no toilet paper at all is beyond comprehension!

As my grandmother (and probably yours too) always said - we don't know we're born!

Labels:

1940s,

advertisement,

Britain,

deprivation,

history,

rationing,

Second World War,

UK,

women's magazine

Sunday, 1 November 2009

Scarves and buckles

Not long ago, I showed a visiting friend a British Pathé film (forgive the regular British Pathé references and links - I'm officially obsessed with it) from 1942 demonstrating some ingenious ways to wear headscarves. We were both filled with enthusiasm and inspiration so I dug out some old scarves for us to experiment with.

First the film, which is well worth the link leap:

My friend tried the 'natty little pussycat' with just one long scarf rather than the two recommended, and was so taken with it she left it on. Some of the other variants were possibly a little too complicated and involved pins so we left those alone (particularly prudent after a couple of glasses of wine).

First the film, which is well worth the link leap:

TURBANS (issue title is WAYS AND MEANS)

My friend tried the 'natty little pussycat' with just one long scarf rather than the two recommended, and was so taken with it she left it on. Some of the other variants were possibly a little too complicated and involved pins so we left those alone (particularly prudent after a couple of glasses of wine).

Labels:

1940s,

British Pathé,

buckle,

film,

instruction,

movie,

scarf

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)