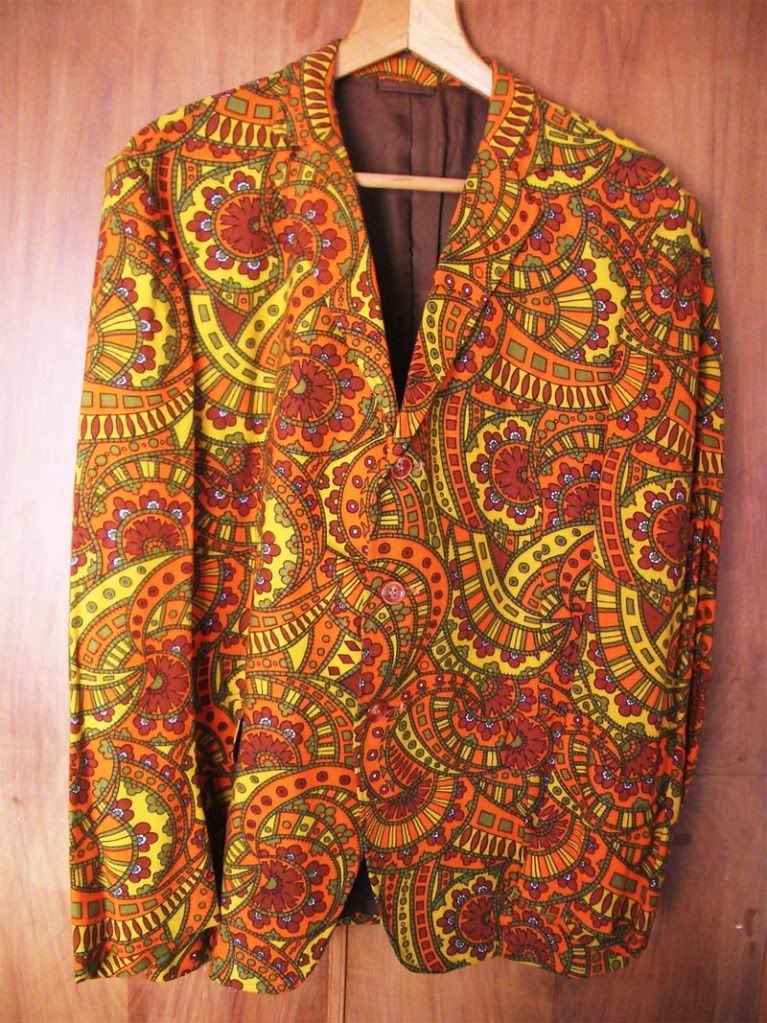

I found this jacket at Stockport's flea market about four years ago. The stall holder told me he bought it for 13 guineas when he was 16 years old from a local menswear shop called The Toggery. Judging by its condition, it looked like there had been few occasions (if any) when he had summoned up sufficient courage to wear it. Its quite a piece.

Of course, I was filled with curiousity about The Toggery so I looked it up online and most of the references I discovered related to the 1960s band The Toggery Five, managed by the proprietor of the shop, Michael Cohen, who obviously supplied their enviable wardrobes as well. Olaf Owre has composed a very thorough account of the band's story, and there's some fabulous pictures of them on the original singer, Frank Renshaw's website. Including this one:

The Toggery Five outside The Toggery, Mersey Square, Stockport, 1964. Picture source The Toggery Five 1963-1966.

Graham Nash of the Hollies had worked there and, in fact, Michael Cohen went on to become their manager too.

This shop was evidently a leading source of ultra fashionable menswear in the north west during the 1960s, and supplied 'fab gear' (apologies, it seemed appropriate!) to numerous local, regional, and not so local, bands. Including the Beatles and the Rolling Stones (allegedly) - we'll come to that soon enough.

The Toggery, it was becoming clear, was an historically significant nexus of the music and fashion scenes of the time, so how come I'd never heard of it?

Anyway, some people I know, of a certain generation, remember The Toggery vividly. My mum worked at a branch of Boots which was opposite The Toggery, and fondly recalls glimpsing the steady procession of handsome young men who patronised the shop. Joe Moss remembers getting his best ever suit from The Toggery in his younger days, not to mention boots and numerous shirts. He also has a friend called Pete Maclaine who used to work there, who was still in touch with Michael Cohen himself.

I wondered if it would be possible to interview Mr Cohen to find out more of this story, and, thanks to the kind efforts of Pete Maclaine, it turned out it was. What follows is material drawn from an interview with Michael Cohen conducted on 5th August 2009, with Pete and Joe in attendance (and sometimes chipping in).

An aside - Pete is a significant player in the Manchester music scene himself. As Pete Maclaine and the Dakotas (later Pete Maclaine and the Clan) he has been a musician for nearly 50 years, and is still going strong. His band were the first from Manchester to play the Cavern in Liverpool, and he has the unusual distinction of having had the Dakotas stolen from under him by Brian Epstein, who installed Billy J. Kramer as the lead singer instead. He has a phenomenal store of anecdotes about the music business and his adventures in it, (this article has a few good ones) not to mention an inexhaustible fund of jokes and patter.

On to the story, which follows after the jump: