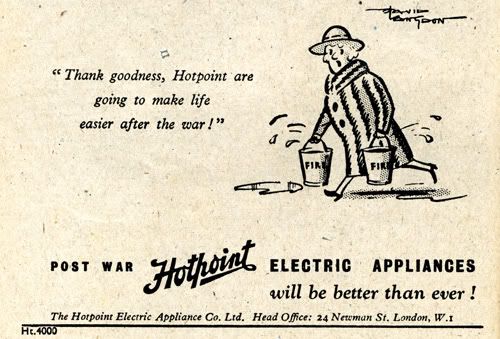

Leafing through a copy of Modern Woman magazine from January 1944, I noticed that a number of the advertisements weren't promoting actual goods, but the promise of them after the war.

The frazzled lady above with the fire buckets is presumably doing the weekly wash, and couldn't wait until she was able to buy a new Hotpoint washing machine, something that I'm sure a lot of women at the time could relate to.

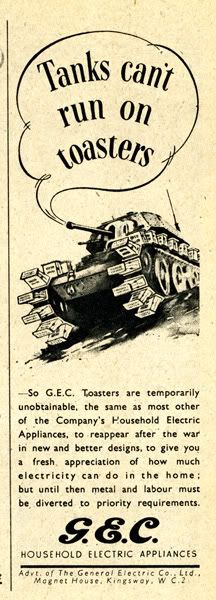

G.E.C. (below) used an arresting illustration to make the point that their production lines were diverted to munitions work for the duration:

Clothing manufacturers, such as Healthguard knitwear, were busy supplying the troops with uniforms and (presumably in this case) cosy and durable knitted sweaters and undergarments, although in this industry, unlike that of the electrical manufacturers, a small proportion of their output was devoted to the domestic market:

The tone is sympathetic but encouraging - acknowledging that their products will be scarce and probably require a concerted effort to hunt around numerous retailers to source - "annoying, perhaps, but well worth the bother." (I can't see that phrase catching on in the same way as "Keep calm and carry on," somehow).

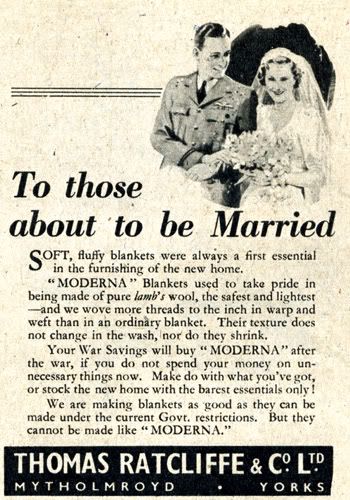

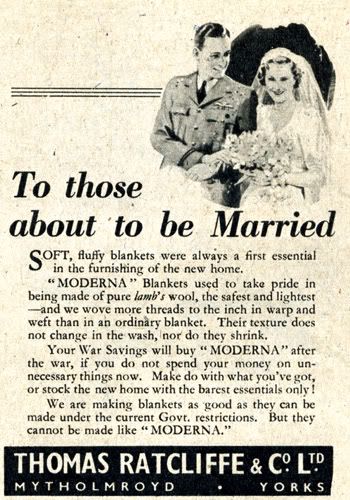

Thomas Ratcliffe & Co. Ltd., makers of Moderna wool blankets, appear concerned to preserve their image as producers of high quality goods:

After explaining what makes their blankets so special - "pure lamb's wool . . . more threads to the inch in warp and weft than in an ordinary blanket" - they are obliged to confess that their wartime blankets, produced "under the current Govt. restrictions," aren't quite so special. In fact, its clear they really don't want to sell you their current, substandard blankets at all and instead urge wartime brides who are setting up their new homes to save their money for the (better) post-war Moderna blankets and in the meantime "make do with what you've got"!

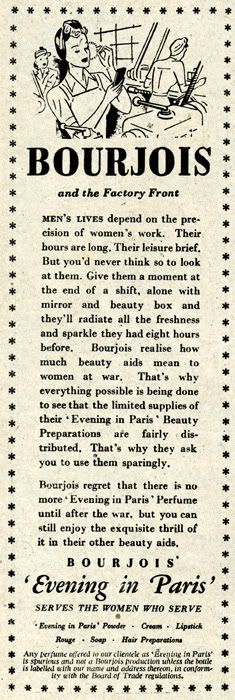

Bourjois, the cosmetics manufacturer, congratulates women on maintaining their feminine allure whilst engaged in arduous war work, but urges them to use their scarce products sparingly:

In small print at the bottom, after expressing regret that their Evening in Paris perfume will not be available during the war, is this warning: "Any perfume offered to our clientele as 'Evening in Paris' is spurious and not a Bourjois production unless the bottle is labelled with our name and address thereon, in conformity with the Board of Trade regulations."

It seems that shoddy, counterfeit goods were another hazard of wartime life.

All these adverts appeared in a single magazine in 1944, five years into the Second World War, and their message must have been repeated throughout countless publications during the conflict. Although manufacturers engaged in essential war production were probably not suffering unduly, with their lucrative Government contracts, they were evidently anxious to maintain public goodwill and the future customer base that would ensure their post war prosperity.

For consumers, it must have been constantly frustrating to be repeatedly reminded about what they didn't have and couldn't get. Everything had to wait until after the war.

But what nobody seemed to realise (or perhaps didn't dare admit) was that all these enticing goods wouldn't suddenly appear in the shops once victory was declared in 1945. In fact, shortages and rationing got much worse! The government had huge wartime debts and just about anything worth selling was exported to help pay it off.

After six long years of deprivation, not to mention the stress and heartbreak of living through a long and bitter world war, the patient and enduring British consumers were faced with a further nine years wait before all rationing finally ended in 1954.

Of course, they weren't necessarily that patient and enduring (who would be?) If you want to learn more about the 'ordinary' British person's experience of the immediate post war years, you can't do better than Simon Garfield's book Our Hidden Lives. Garfield skilfully and sensitively edits the Mass Observation diaries of five people to illustrate how this largely overlooked era affected those five individuals, and it makes surprisingly vivid and compelling reading.

An aspect of wartime advertising I haven't mentioned yet, is the manufacturers' awareness of the limits of that assumed patience. An Atkinsons Eau de Cologne ad pleads: "Supplies are scarce though, so please don't be cross if the shopkeeper is out of stock." A Parozone bleach ad urges: "Don't blame your suppliers if you can't get all the Parazone you want. Bear with us please - we are doing everything possible to maintain supplies."

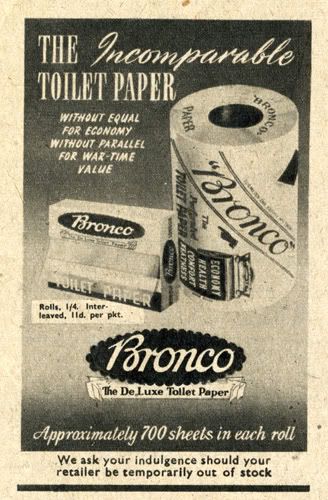

There's a clear hint of the daily, small-scale conflicts that poor, hard-pressed shop staff had to face from frustrated and enraged shoppers. But, I ask you, could you tolerate this?:

At the bottom of this advertisement it says: "We ask your indulgence should your retailer be temporarily out of stock." My memories of Bronco are of the waxy, stiff and resolutely non-absorbent toilet paper that no-one would buy or use out of choice. To have only Bronco toilet paper available is torture enough. To have no toilet paper at all is beyond comprehension!

At the bottom of this advertisement it says: "We ask your indulgence should your retailer be temporarily out of stock." My memories of Bronco are of the waxy, stiff and resolutely non-absorbent toilet paper that no-one would buy or use out of choice. To have only Bronco toilet paper available is torture enough. To have no toilet paper at all is beyond comprehension!

As my grandmother (and probably yours too) always said - we don't know we're born!

2 comments:

What a fascinating article! The advertisers were so clever AND creative during THE War! Maybe their conservation initiatives should be closely researched for The Present! Thanks again for informing and gently reminding us about the strength/restraint of our ancestors. No whining allowed!

xox bb

I think for most people, trying to cope with what our grandparents had to would be unthinkable! Channel 4 did a series a while ago called the 1940s House, where they took a family and made them live like it was the Second World War. I didn't see much of it, but I think there was a lot of grumbling involved!

And yes, we've a lot to learn from their thrifty ways and 'making do and mending'!

Post a Comment